Michael Everson of Evertype Publishing writes:

Dea-scéala! Foilseofar aistriúchán Gaeilge Nicholas Williams den leabhar "An

Hobad" ar deireadh thiar ar an 25 Márta 2012. Beidh clúdach crua air, arna chló

maille le léaráidí daite agus léarscáileanna. Más mian leat réamhordú a chur

isteach, cuirtear ríomhphost chugam agus beidh mé i dteagmháil leat maidir leis

na sonraí cuí.

Great news! Nicholas Williams' translation of "The Hobbit"

into Irish will be published at long last on 25 March 2012. The book will be

hardcover, printed with colour illustrations and maps. If you would like to

pre-order a copy, send me and e-mail and I will contact you with

details.

Michael Everson * everson@evertype.com * http://www.evertype.com

Cnoc Sceichín *

Leac an Anfa * Cathair na Mart * Maigh Eo * Éire

Friday, January 20, 2012

Thursday, January 19, 2012

2011 and Some Nobel Thoughts

Last year I had two ancient projects finally see the light of day, and one of my books came out as an ebook. One of the ancient projects was Tolkien-related, the other not. The Tolkien-related piece was a short filler article I submitted back in 2006 to CSL: The Bulletin of The New York C.S. Lewis Society. The two-page piece is titled "The Inklings and Festschriften", and merely surveys the eleven books published to honor nine of the Inklings. It appears in the May/June 2011 issue. For information on the New York C. S. Lewis Society, see their web page. The older book that re-appeared as an ebook is my anthology H.P. Lovecraft's Favorite Weird Tales. (Clicking on the cover at right will take you to kindle version at Amazon. I believe other e-formats were in the works, so check your favorite platform. The print edition is still also available here.) The project unrelated to Tolkien was an expanded edition of a 1933 collection, titled Devils' Drums, of central-African voodoo-styled horror stories by British writer Vivian Meik. This book was completed back in 2003 for one publisher, who sat on it for eight years until I pulled it and placed it with a different publisher, Medusa Press, who produced a fine edition, limited to 300 copies. For further details on the new edition, see Medusa Press's website. For further information on Vivian Meik, see my entry on him at my Lesser-Known Writers blog by clicking here.

And speaking of my Lesser-Known Writers blog, I should point out that a couple of the entries already posted have Tolkienian associations. There is an entry on Dora Owen, who edited The Book of Fairy Poetry (1920) in which Tolken's poem "Goblin Feet" was first reprinted, along with an original color illustration by Warwick Goble. And there is an entry on G.S. Tancred, who edited the slim 1927 poetry volume Realities which contains the first publication of Tolkien's poem "The Nameless Land". There are more entries on writers with Tolkien-associations in the queue to be published, and in the entries being worked on, so check back. I'm using the Labels function of the blog as a kind of index to it, so if you scan down to Tolkien, and click on it, you'll find the Tolkien-related posts (currently two in number). Here are the direct-to-entry links for the entries on Dora Owen and G.S. Tancred.

A number of interesting publications relating to Tolkien came out last year. Most of these have received (or will receive) good coverage elsewhere, so I'd just like to call attention to a few off-trail items that might otherwise escape under the radar. These are the first two issues of a new (paperback) serial, The Journal of Inklings Studies. So far, the Tolkien-related content has been minimal (amounting to one book review by Jason Fisher), but the C.S. Lewis content has been very interesting, and I hope we will see the Tolkien coverage expand proportionally in future issues. Details and contents listings at the publisher's website.

Michael Saler's As If, discussed in a previous post, is now out. ***UPDATE, 1/20: Tom Shippey has reviewed As If in The Wall Street Journal, see it here*** Similarly, Paul Edmund Thomas's new edition of E. R. Eddison's Styrbiorn the Strong, also previously discussed, made its appearance in December. Oddly, the publisher photographed the main text from the 1926 Boni edition, and set the new material in a different font, making for an inelegant hybrid. But that's a minor complaint compared to the good news that this book is available again.

Finally, a few comments on the news reported by Alison Flood in The Guardian that Tolkien was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1961. I've seen a lot of snarky comments, the worst of which is probably The Guardian's own headline: "J.R.R. Tolkien's Nobel Prize Chances Dashed by 'Poor Prose'" . The Guardian has a history of knocking Tolkien at almost every opportunity, but the article below the headline says something quite different from what the headline implies, AND if you look into the source in the Swedish original, you find the situation is more complicated than the sneering newspaper headline implies.

First of all, we already knew that on 7 January 1961, C. S. Lewis wrote to Alastair Fowler:

The article in the Swedish newspaper which broke the news, the Sydsvenska Dagbladet, can be found here. I'm grateful to the Swedish translator John-Henri Holmberg for commenting on this and allowing me to quote him here. John-Henri writes:

This leaves one to wonder if Österling dismissed Tolkien based on having seen only Ohlmark's Swedish translation (or only a volume or two of it, since the translation of the third volume had not apparently been published). John-Henri Holmberg comments:

And speaking of my Lesser-Known Writers blog, I should point out that a couple of the entries already posted have Tolkienian associations. There is an entry on Dora Owen, who edited The Book of Fairy Poetry (1920) in which Tolken's poem "Goblin Feet" was first reprinted, along with an original color illustration by Warwick Goble. And there is an entry on G.S. Tancred, who edited the slim 1927 poetry volume Realities which contains the first publication of Tolkien's poem "The Nameless Land". There are more entries on writers with Tolkien-associations in the queue to be published, and in the entries being worked on, so check back. I'm using the Labels function of the blog as a kind of index to it, so if you scan down to Tolkien, and click on it, you'll find the Tolkien-related posts (currently two in number). Here are the direct-to-entry links for the entries on Dora Owen and G.S. Tancred.

A number of interesting publications relating to Tolkien came out last year. Most of these have received (or will receive) good coverage elsewhere, so I'd just like to call attention to a few off-trail items that might otherwise escape under the radar. These are the first two issues of a new (paperback) serial, The Journal of Inklings Studies. So far, the Tolkien-related content has been minimal (amounting to one book review by Jason Fisher), but the C.S. Lewis content has been very interesting, and I hope we will see the Tolkien coverage expand proportionally in future issues. Details and contents listings at the publisher's website.

Michael Saler's As If, discussed in a previous post, is now out. ***UPDATE, 1/20: Tom Shippey has reviewed As If in The Wall Street Journal, see it here*** Similarly, Paul Edmund Thomas's new edition of E. R. Eddison's Styrbiorn the Strong, also previously discussed, made its appearance in December. Oddly, the publisher photographed the main text from the 1926 Boni edition, and set the new material in a different font, making for an inelegant hybrid. But that's a minor complaint compared to the good news that this book is available again.

Finally, a few comments on the news reported by Alison Flood in The Guardian that Tolkien was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1961. I've seen a lot of snarky comments, the worst of which is probably The Guardian's own headline: "J.R.R. Tolkien's Nobel Prize Chances Dashed by 'Poor Prose'" . The Guardian has a history of knocking Tolkien at almost every opportunity, but the article below the headline says something quite different from what the headline implies, AND if you look into the source in the Swedish original, you find the situation is more complicated than the sneering newspaper headline implies.

First of all, we already knew that on 7 January 1961, C. S. Lewis wrote to Alastair Fowler:

In confidence. If you were asked to nominate a candidate for the Nobel Prize (literature), who wd. be your choice? Mauriac has had it. Frost? Eliot? Tolkien? E.M. Forster? Do you know the ideological slant (if any) of the Swedish Academy? Keep all this under your hat.What we learned this month, after the fifty-year embargo on the 1961 Nobel discussions was lifted, is that C. S. Lewis, who as a professor of literature was apparently asked to nominate a candidate, did in fact nominate J.R.R. Tolkien. It was the Nobel jury-member Anders Österling who nixed Tolkien from consideration, as he did several other names proffered.

The article in the Swedish newspaper which broke the news, the Sydsvenska Dagbladet, can be found here. I'm grateful to the Swedish translator John-Henri Holmberg for commenting on this and allowing me to quote him here. John-Henri writes:

What Anders Österling wrote about Tolkien was that "resultatet har dock icke i något avseende blivit diktning av högsta klass”, which is actually difficult to translate. Literally, I might try: "The result, however, has in no particular turned out to be 'diktning' of the highest order", but the problem is the word "diktning", which is both a noun and a verb. As a noun, it means "literary creation, poetry, poetics"; as a verb it means "the creation of poetry, the act of literary creation" etc. Make of it what you will; as a Swede, I'd say that the sense isn't really that Österling (himself a poet and literary critic, in his late 70s in 1961 though he remained active until around 1978) isn't primarily complaining about Tolkien's prose, but of the totality of his literary creation: what he says is that as a whole, The Lord of the Rings just isn't up to par.Which is of course not what The Guardian says. But to put further context on this, it should be pointed out that the Swedish translation of The Lord of the Rings was then just appearing (the first volume in 1959, and the third later in 1961). The translation was by Åke Ohlmarks, and Tolkien himself knew enough Swedish to complain of Ohlmark's translation ("guilty of some very strange mistakes") and of the "ridiculous fantasy" that Ohlmarks constructed as a biographical introduction (see Tolkien's letters to Allen & Unwin of 24 January and 23 February 1961, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien).

This leaves one to wonder if Österling dismissed Tolkien based on having seen only Ohlmark's Swedish translation (or only a volume or two of it, since the translation of the third volume had not apparently been published). John-Henri Holmberg comments:

Incidentally, sure, by now the members of the Academy probably are reasonably fluent in English. Maybe not as much in 1961; remember that Sweden was primarily influenced from Germany during the later 1900s and until WWII. The first and obligatory foreign language taught in Swedish schools was German, until and including the Spring term of 1944; since the Fall term that year, it's been English. Which means that Swedes older than around 30 in 1961 didn't necessarily study much English in schoolAnd about the dismissal of Tolkien, John-Henri wrote further:

The writer expressing this view, the then Constant Secretary of the Swedish Academy, Anders Österling, himself a poet (1884-1981), was already 77 in 1961 (possibly ironic, considering his views on the age of some Nobel award candidates; he continued publishing almost until his death), and had been greatly influenced by Henri Bergson as well as by the British romantic poets. In fact, Österling was quite impressive both as a poet and as a critic; his active work spanned some 75 years, as his first book of poems was published in 1904 and his last in 1978. As a critic, he was famous for his extremely high literary demands, but he remained open to new forms of expression in the arts; in his mid-eighties, in the early 1970s, he wrote appreciatively of psychedelic and hippie culture.To me, the most newsworthy aspect of this revelation is not that Tolkien was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1961, nor that he didn't win it (the Swedish Academy has a long history of eclectic choices), but that given this small bit of Tolkien-related news those at The Guardian jumped at the opportunity to twist it and sneer. Shame on them.

Sunday, December 4, 2011

Tolkien: As If

A quick post here to say that Michael Saler's long-awaited book, As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality, is on the threshold of publication. I say threshold because the Kindle edition is currently available (click here), and the hardcover and trade paperback versions, published by Oxford University Press, are due imminently. (The author tells me that Amazon says the publication date is January 9th, but he's just got his own copies so it should be shipping sooner.)

The hifalutin subtitle, "modern enchantment and the literary prehistory of virtual reality", mainly refers to the idea of modern imaginary worlds, in which authors and their readers share in willing suspension of disbelief. So the book covers the Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories, H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, and Tolkien's Middle-earth. The book examines how fans began to inhabit imaginary worlds persistently and communally starting in the late 19th century, in effect transforming them into virtual worlds that presaged contemporary virtual reality.

I read the Tolkien chapter in advance, and can say it represents a fascinating look at Tolkien from the outside looking in (i.e., culturally and historically), rather than (what is usual in Tolkien studies) from the inside looking at the details or the literary background of specific aspects of Tolkien's invented world. The trade paperback is currently priced at $27.95 (though who knows if Amazon may discount it after publication). Recommended.

**Update 12/12** The trade paperback is now in stock. Click here for the Amazon page.

The hifalutin subtitle, "modern enchantment and the literary prehistory of virtual reality", mainly refers to the idea of modern imaginary worlds, in which authors and their readers share in willing suspension of disbelief. So the book covers the Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories, H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, and Tolkien's Middle-earth. The book examines how fans began to inhabit imaginary worlds persistently and communally starting in the late 19th century, in effect transforming them into virtual worlds that presaged contemporary virtual reality.

I read the Tolkien chapter in advance, and can say it represents a fascinating look at Tolkien from the outside looking in (i.e., culturally and historically), rather than (what is usual in Tolkien studies) from the inside looking at the details or the literary background of specific aspects of Tolkien's invented world. The trade paperback is currently priced at $27.95 (though who knows if Amazon may discount it after publication). Recommended.

**Update 12/12** The trade paperback is now in stock. Click here for the Amazon page.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Evangeline Walton News

For some time now I have been working with Evangeline Walton's literary heir, Debra L. Hammond, both in sorting the archive of papers and in preparing new Walton publications. Some of the first fruits have begun to appear, so I'd like to bring notice to them here.

First, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction has just published a new short story we found in Walton's papers, "They That Have Wings". It appears in the November/December 2011 issue. Some reader comments about this issue can be found here. Also, I was interviewed about Evangeline Walton for the F&SF blog, and was able to expand on other Walton projects that are in the works. See it here.

It is mentioned in the interview, but I'd also like to call attention here to the new website evangelinewalton.com where further information can be found. We will post further news there as things develop.

First, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction has just published a new short story we found in Walton's papers, "They That Have Wings". It appears in the November/December 2011 issue. Some reader comments about this issue can be found here. Also, I was interviewed about Evangeline Walton for the F&SF blog, and was able to expand on other Walton projects that are in the works. See it here.

It is mentioned in the interview, but I'd also like to call attention here to the new website evangelinewalton.com where further information can be found. We will post further news there as things develop.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Tolkien and the Newman Association

A while ago I stumbled on a reference to a letter, co-signed by Tolkien, published in The Times for Friday, 28 January 1949 (page 5). This letter isn't referenced in any of the usual sources, so it makes for a minor discovery. The letter is signed by Tolkien and nine others, comprising the Honorary President of the Newman Association and nine Honorary Vice Presidents, the latter including Tolkien. The letter registers protest at the arrest of the Cardinal Primate of Hungary by the Hungarian government.

Tolkien's affiliation with the Newman Association was previously undocumented. The Newman Association was founded in 1942, and continues to this day. (See their website here.) Tolkien's involvement does not seem to have been extensive. I am grateful to Dr. Christopher Quirke, Secretary of the Newman Association for looking into the matter and conferring with his colleagues. He reports: "I made enquiries and saw numerous letter headed paper for the Association during its early years and Tolkien's name does appear in a long list of Vice Presidents that we appeared to have during those early years. The Association was founded in 1942, for Catholic university graduates, and Oxford was prominent at its foundation. I can't say more than that. I don't know, for example, how involved he was with the Oxford circle."

Tolkien was unquestionably very busy professionally all throughout the 1940s, but it's interesting to note that for a time at least he managed some additional volunteer work for the Association devoted to John Henry Newman, founder of the Birmingham Oratory where Tolkien himself had been educated as a boy.

Tolkien's affiliation with the Newman Association was previously undocumented. The Newman Association was founded in 1942, and continues to this day. (See their website here.) Tolkien's involvement does not seem to have been extensive. I am grateful to Dr. Christopher Quirke, Secretary of the Newman Association for looking into the matter and conferring with his colleagues. He reports: "I made enquiries and saw numerous letter headed paper for the Association during its early years and Tolkien's name does appear in a long list of Vice Presidents that we appeared to have during those early years. The Association was founded in 1942, for Catholic university graduates, and Oxford was prominent at its foundation. I can't say more than that. I don't know, for example, how involved he was with the Oxford circle."

Tolkien was unquestionably very busy professionally all throughout the 1940s, but it's interesting to note that for a time at least he managed some additional volunteer work for the Association devoted to John Henry Newman, founder of the Birmingham Oratory where Tolkien himself had been educated as a boy.

Monday, November 21, 2011

Dale Nelson's Summation on Tolkien in pre-1970 blurbs

Dale Nelson sent a nice summation of the situation with Tolkien and pre-1970 blurbs, and with his permission I pass it along here:

**

Well, Doug, I'm to the point of saying the survey is done so far as I expect to be able to take it, barring any lucky further discoveries.

Here are my conclusions:

a.Thirteen paperbacks referred to Tolkien and/or The Lord of the Rings on front or back cover.

b.Lancer led the way with Tolkienian marketing, using it on 5 of their books.

c.An American fan of Tolkien just looking at paperback cover blurbs would be led to the following:

--5 works of genuine high fantasy for adults: Eddison's Worm Ouroboros and Mistress of Mistresses, Morris's Wood Beyond the World, Dunsany's King of Elfland's Daughter (all Ballantine); Pratt's Well of the Unicorn (Lancer);

--2 Tolkienian fantasies for children: Garner's The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath (Ace)

--4 works of swords-and-sorcery: Howard's Conan the Adventurer and Conan the Conqueror (Lancer); de Camp's Tritonian Ring (Paperback Library); Moorcock's Jewel in the Skull (Lancer)

--1 work of fantasy that I'm not prepared to put into any of the categories above: Hubbard's Slaves of Sleep (Lancer)

--1 work of science fiction: Herbert's Dune (Ace)

It seems to me that publishers were slow to distinguish Tolkienian fantasy or high fantasy from other kinds of fantasy. Put another way, I suspect that American paperback publishers clearly differentiated science fiction from fantasy, but that was as fine a distinction as they were prepared to make for several years.

Publishers seem to have been a bit slow to catch on to the idea of multi-volume fantasy cycles. Ballantine's Eddison books are referred to as a "group." Lancer's Jewel in the Skull is heralded as "the first of a series destined to rank with... the Lord of the Rings trilogy." As un-Tolkienian as this book (and its author) were, it might be considered to be the one that comes closest to alluding to the idea of a multi-volume fantasy work with continuing characters and so on; or it might be "tied" for this with Eddison. (NB I haven't seen the two middle books yet; I don't think they allude to Tolkien, but perhaps they do.) To my eye, the cover design of the Eddison books is most "Tolkienian" (in so markedly looking like Ballantine's Tolkien set).

**

Thanks, Dale!

With regard to the distinction in the 1950s and 1960s between fantasy and science fiction, I'm not sure American publishers were any clearer than British ones. Remember the blurb (by Naomi Mitchison) on the original edition of The Fellowship of the Ring that called it "super-science-fiction"? I've always thought that an odd description, and recently came across a good contemporary explanation of this usage. In Basil Davenport's Inquiry into Science Fiction (1955), he wrote:

Basil Davenport (1905-1966) was one of the first heavyweight literary critics to proclaim the worth of science fiction as literature. He served for many years on the Editorial Board of the Book-of-the-Month Club, and published his short book on science fiction in 1955, five years before Kingsley Amis's New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (1960). One of Davenport's first books was a companion to Austin Tappan Wright's Islandia, An Introduction to Islandia (1942). He also introduced the omnibus of five novels by Olaf Stapledon, To the End of Time (1953) and edited some anthologies of science fiction and horror.

An interesting sidelight of Davenport's comment is the idea that Mitchison meant Tolkien's work to be seen as imaginative writing (super-science-fiction)of a type that one needn't be ashamed to be seen reading---whereas the implied derision is that one should feel ashamed to be seen reading regular science fiction. Such bone-headed attitudes persist to this day, but are thankfully less common. Even Margaret Atwood has finally admitted that she writes science fiction!

**

Well, Doug, I'm to the point of saying the survey is done so far as I expect to be able to take it, barring any lucky further discoveries.

Here are my conclusions:

a.Thirteen paperbacks referred to Tolkien and/or The Lord of the Rings on front or back cover.

b.Lancer led the way with Tolkienian marketing, using it on 5 of their books.

c.An American fan of Tolkien just looking at paperback cover blurbs would be led to the following:

--5 works of genuine high fantasy for adults: Eddison's Worm Ouroboros and Mistress of Mistresses, Morris's Wood Beyond the World, Dunsany's King of Elfland's Daughter (all Ballantine); Pratt's Well of the Unicorn (Lancer);

--2 Tolkienian fantasies for children: Garner's The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath (Ace)

--4 works of swords-and-sorcery: Howard's Conan the Adventurer and Conan the Conqueror (Lancer); de Camp's Tritonian Ring (Paperback Library); Moorcock's Jewel in the Skull (Lancer)

--1 work of fantasy that I'm not prepared to put into any of the categories above: Hubbard's Slaves of Sleep (Lancer)

--1 work of science fiction: Herbert's Dune (Ace)

It seems to me that publishers were slow to distinguish Tolkienian fantasy or high fantasy from other kinds of fantasy. Put another way, I suspect that American paperback publishers clearly differentiated science fiction from fantasy, but that was as fine a distinction as they were prepared to make for several years.

Publishers seem to have been a bit slow to catch on to the idea of multi-volume fantasy cycles. Ballantine's Eddison books are referred to as a "group." Lancer's Jewel in the Skull is heralded as "the first of a series destined to rank with... the Lord of the Rings trilogy." As un-Tolkienian as this book (and its author) were, it might be considered to be the one that comes closest to alluding to the idea of a multi-volume fantasy work with continuing characters and so on; or it might be "tied" for this with Eddison. (NB I haven't seen the two middle books yet; I don't think they allude to Tolkien, but perhaps they do.) To my eye, the cover design of the Eddison books is most "Tolkienian" (in so markedly looking like Ballantine's Tolkien set).

**

Thanks, Dale!

With regard to the distinction in the 1950s and 1960s between fantasy and science fiction, I'm not sure American publishers were any clearer than British ones. Remember the blurb (by Naomi Mitchison) on the original edition of The Fellowship of the Ring that called it "super-science-fiction"? I've always thought that an odd description, and recently came across a good contemporary explanation of this usage. In Basil Davenport's Inquiry into Science Fiction (1955), he wrote:

Recently there appeared a book called The Fellowship of the Ring, which, though intended for an adult audience, is pure fairy tale; its characters are elves and enchanters (and not a hint of a gene or a chromosome among the lot) but even that carries on the jacket a quote saying, "This is really super-science-fiction." That is, of course, sheer nonsense; it is hard to know where to draw the line defining science fiction, but it certainly excludes The Fellowship of the Ring. What the critic actually means is, "This is imaginative writing, but you needn't be ashamed to be seen reading it." (pp. 79-80)

Basil Davenport (1905-1966) was one of the first heavyweight literary critics to proclaim the worth of science fiction as literature. He served for many years on the Editorial Board of the Book-of-the-Month Club, and published his short book on science fiction in 1955, five years before Kingsley Amis's New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (1960). One of Davenport's first books was a companion to Austin Tappan Wright's Islandia, An Introduction to Islandia (1942). He also introduced the omnibus of five novels by Olaf Stapledon, To the End of Time (1953) and edited some anthologies of science fiction and horror.

An interesting sidelight of Davenport's comment is the idea that Mitchison meant Tolkien's work to be seen as imaginative writing (super-science-fiction)of a type that one needn't be ashamed to be seen reading---whereas the implied derision is that one should feel ashamed to be seen reading regular science fiction. Such bone-headed attitudes persist to this day, but are thankfully less common. Even Margaret Atwood has finally admitted that she writes science fiction!

Monday, July 11, 2011

Pre-1970 Paperbacks with Comparisons to Tolkien

**updated entry**

Thanks in particular to Dale Nelson, and a few others who emailed me, I can now post a follow-up on what books published before 1970 have blurbs with comparisons to Tolkien. There are no hardcovers here simply because I don't know of any, and no one suggested any **but see the comments below**. Here are the results, chronologically (and subject to future revision!):

1965: The Ace edition of Alan Garner's The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. Interestingly, Ace had published their pirated edition of The Lord of the Rings in May (volume one) and July (volumes two and three) of 1965. The three volumes have cover art by Jack Gaughan, as does the Ace edition (G-570) of The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. The blurb here merely calls the book "a fantastic novel in the Tolkien tradition."

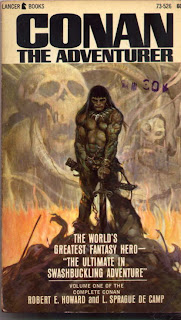

1966 brings us two candidates. The first published was probably Conan the Adventurer (Lancer Books, 63-526), by Robert E. Howard and L. Sprague de Camp. The front cover (with artwork by Frank Frazetta) doesn't make any comparion to Tolkien, but on the rear cover it says in large letters: "Adventures more imaginative than 'Lord of the Rings'". Conan the Adventurer was the first of an eleven volume series, but it is the only one with a blurb mentioning Tolkien's works.

The other candidate from 1966 is bibliographically confusing, and sometimes erroneously dated to 1965. This is the Ace Books edition of Frank Herbert's Dune, published in hardcover by Chilton in 1965. (Tolkien was sent a copy of the book by its editor at Chilton, Sterling Lanier, an author in his own right and a correspondent of Tolkien's. When the British edition of the book was to be published in 1966, the British publisher Gollancz also sent Tolkien a copy of the book, requesting a blurb. Tolkien declined, saying he found the book too distasteful.) The paperback edition of Dune published by Ace Books is undated, but on the cover it highlights the fact that the book was the "Winner of the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award for Best Science Fiction Novel of the Year". The Nebula Award's banquet had been held on March 11,1966, where the first Nebula Awards were presented by the recently-formed organization of Science Fiction Writers of America. The Hugo Award was announced at the 24th World Science Fiction Convention, held in Cleveland, Ohio, from September 1st-5th, 1966. Thus, by these dates, the Ace Book edition of Dune could not have come out until around the end of 1966. The mention of Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings comes in a blurb by Arthur C. Clarke on the rear cover, where he says of Dune: "I know nothing comparable to it except The Lord of the Rings." (Clarke himself was an acquaintance of Tolkien's. Sometime in the mid-1950s they had lunched together with C.S. Lewis in Oxford, and Clarke spoke again with Tolkien in September 1957 when Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings was presented with an International Fantasy Award, just following the 15th World Science Fiction Convention held in London.)

And next we have another Alan Garner book, again published by Ace (G-753), The Moon of Gomrath. On the back cover, it says "Here, told with the talent of a Tolkien and the wonder of an Andre Norton, is what befell the two Earthlings . . ." At the bottom of the rear cover there is a bizarre quotation from a review (presumably of the hardcover edition of 1965) that was published in The New York Times: "From one Tolkien shiver to another, there is a gripping power to these episodes." The front cover art is by the late Jeffrey Catherine Jones (1944-2011).

The final book comes from 1969. Nancy Martsch (via Dale Nelson) noticed that I missed one occurrance of a Tolkien-related blurb in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. The July 1969 Ballantine edition of William Morris's The Wood beyond the World has a phrase in the back cover, noting that "William Morris has been described as 'obviously a Nineteenth Century Tolkien . . .' " The blurb is backgrounded by some foliage in Gervasio Gallardo's typical style, as is often fond in his many glorious covers for the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. I do not know where the "obviously a Nineteenth Century Tolkien" quote comes from, but it sounds rather like Lin Carter, the "Consulting Editor" (not the Editor, who was Betty Ballantine) of the whole Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, which ran from 1969 to 1974. I plan to post a bunch of my work-in-progress on this series in the future.

One last notice here. Thomas Kent Miller suggested the Curtis Books edition of Edison Marshall's The Lost Land (originally published as Dian of the Lost Land by Chilton in 1968), but the undated edition by Curtis Books seems to have come out in 1972 (Curtis Books in fact published only between 1971-74), so that rules it out. The blurb on it says: "A Thrilling journey to a world beyond Middle Earth and Narnia". Here, at least, is an early misspelling of Middle-earth, a common error which continues to this day in major news organizations like The New York Times, which can never get it right. But a look at the wraparound cover for The Lost Land is still in order, for it's another Gervasio Gallardo cover, one of his more surreal types, but a Gallardo nonetheless, and one that isn't often seen.

Interestingly, the bulk of these early blurbs seem to have originated with people who had some connections with Tolkien. Betty and Ian Ballantine published The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings with their firm in 1965. The editor at Ace Books who published the pirated edition of The Lord of the Rings in 1965, and who published the Alan Garner books, was Donald A. Wollheim. Though he professed himself to be no great fan of Tolkien's, Wollheim knew what sold, and was happy to supply book-buyers with what he expected would sell. L. Sprague de Camp was another acquaintance of Tolkien's. They began corresponding in 1963 and Tolkien entertained de Camp at his house in February 1967, as de Camp was returning to the U.S. from a trip to the Middle East and India. Tolkien's acquaintance with Arthur C. Clarke and Sterling Lanier I have mentioned above, but one can also add Alan Garner's name to those connected to Tolkien. Garner was a student at Magdalen College, Oxford, in the mid-1950s, and has acknowledged that he met both Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, though Garner claims that Tolkien's writings had no influence on him. Many readers question this assertion.

Addenda: Thanks again to Dale Nelson, we now have three more entries for 1967. I don't have the months of publication for these titles, so the order given here is random. But all three are from Lancer Books, a mass market company that published around 2,000 titles from 1962 to 1973. The editor (after 1965) was Larry T. Shaw, who had edited a number of science fiction magazines in the mid-1950s. The first is L. Ron Hubbard's Slaves of Sleep (Lancer 73-573).

The requisite blurb is on the rear, and reads: "SLAVES OF SLEEP is a magic carpet into adventure, romance, fantasy, and dazzling color. It rates a place on your shelves next to the works of Tolkien, Burroughs, and Robert E. Howard."

The next is a book by arch-Tolkien basher Michael Moorcock, The Jewel in the Skull (Lancer 73-688). I don't have a scan of the back cover, where the blurb concludes: "a stirring new saga of swords and sorcery by a brilliant writer, the first of a series destined to rank with the Conan series and the Lord of the Rings trilogy."

And finally, another Conan book, The Hour of the Dragon (Lancer 73-572), by Robert E. Howard and edited by the ubiquitous L. Sprague de Camp. The blub on the front cover reads (somewhat ungrammarically): "Howard's only book-length novel, worthy to stand beside such heroic fantasy as E. R. Eddison and J. R. R. Tolkien."

Thanks in particular to Dale Nelson, and a few others who emailed me, I can now post a follow-up on what books published before 1970 have blurbs with comparisons to Tolkien. There are no hardcovers here simply because I don't know of any, and no one suggested any **but see the comments below**. Here are the results, chronologically (and subject to future revision!):

1965: The Ace edition of Alan Garner's The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. Interestingly, Ace had published their pirated edition of The Lord of the Rings in May (volume one) and July (volumes two and three) of 1965. The three volumes have cover art by Jack Gaughan, as does the Ace edition (G-570) of The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. The blurb here merely calls the book "a fantastic novel in the Tolkien tradition."

1966 brings us two candidates. The first published was probably Conan the Adventurer (Lancer Books, 63-526), by Robert E. Howard and L. Sprague de Camp. The front cover (with artwork by Frank Frazetta) doesn't make any comparion to Tolkien, but on the rear cover it says in large letters: "Adventures more imaginative than 'Lord of the Rings'". Conan the Adventurer was the first of an eleven volume series, but it is the only one with a blurb mentioning Tolkien's works.

The other candidate from 1966 is bibliographically confusing, and sometimes erroneously dated to 1965. This is the Ace Books edition of Frank Herbert's Dune, published in hardcover by Chilton in 1965. (Tolkien was sent a copy of the book by its editor at Chilton, Sterling Lanier, an author in his own right and a correspondent of Tolkien's. When the British edition of the book was to be published in 1966, the British publisher Gollancz also sent Tolkien a copy of the book, requesting a blurb. Tolkien declined, saying he found the book too distasteful.) The paperback edition of Dune published by Ace Books is undated, but on the cover it highlights the fact that the book was the "Winner of the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award for Best Science Fiction Novel of the Year". The Nebula Award's banquet had been held on March 11,1966, where the first Nebula Awards were presented by the recently-formed organization of Science Fiction Writers of America. The Hugo Award was announced at the 24th World Science Fiction Convention, held in Cleveland, Ohio, from September 1st-5th, 1966. Thus, by these dates, the Ace Book edition of Dune could not have come out until around the end of 1966. The mention of Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings comes in a blurb by Arthur C. Clarke on the rear cover, where he says of Dune: "I know nothing comparable to it except The Lord of the Rings." (Clarke himself was an acquaintance of Tolkien's. Sometime in the mid-1950s they had lunched together with C.S. Lewis in Oxford, and Clarke spoke again with Tolkien in September 1957 when Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings was presented with an International Fantasy Award, just following the 15th World Science Fiction Convention held in London.)

On to 1967, for which we have two entries **for three more entries, see addenda at bottom**, both books by E. R. Eddison and both published by Ballantine. In April 1967 The Worm Ouroboros was published, and the front cover says "an epic fantasy to compare with Tolkien's 'Lord of the Rings'." (For the cover illustration see my previous post.) Published in August 1967, Eddison's Mistress of Mistresses has a back cover blurb stating: "The second volume in the fantasy classic most often compared with J. R. R. Tolkien."

1968 brings another two examples, the first being the Paperback Library edition of L. Sprague de Camp's The Tritonian Ring, with a cover by Frank Frazetta. Here is the first real blurb that aims directly at Tolkien's readers: "Thrilling sword and sorcery for the fans of Tolkien's 'Lord of the Rings.'"

The final book comes from 1969. Nancy Martsch (via Dale Nelson) noticed that I missed one occurrance of a Tolkien-related blurb in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. The July 1969 Ballantine edition of William Morris's The Wood beyond the World has a phrase in the back cover, noting that "William Morris has been described as 'obviously a Nineteenth Century Tolkien . . .' " The blurb is backgrounded by some foliage in Gervasio Gallardo's typical style, as is often fond in his many glorious covers for the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. I do not know where the "obviously a Nineteenth Century Tolkien" quote comes from, but it sounds rather like Lin Carter, the "Consulting Editor" (not the Editor, who was Betty Ballantine) of the whole Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, which ran from 1969 to 1974. I plan to post a bunch of my work-in-progress on this series in the future.

One last notice here. Thomas Kent Miller suggested the Curtis Books edition of Edison Marshall's The Lost Land (originally published as Dian of the Lost Land by Chilton in 1968), but the undated edition by Curtis Books seems to have come out in 1972 (Curtis Books in fact published only between 1971-74), so that rules it out. The blurb on it says: "A Thrilling journey to a world beyond Middle Earth and Narnia". Here, at least, is an early misspelling of Middle-earth, a common error which continues to this day in major news organizations like The New York Times, which can never get it right. But a look at the wraparound cover for The Lost Land is still in order, for it's another Gervasio Gallardo cover, one of his more surreal types, but a Gallardo nonetheless, and one that isn't often seen.

Interestingly, the bulk of these early blurbs seem to have originated with people who had some connections with Tolkien. Betty and Ian Ballantine published The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings with their firm in 1965. The editor at Ace Books who published the pirated edition of The Lord of the Rings in 1965, and who published the Alan Garner books, was Donald A. Wollheim. Though he professed himself to be no great fan of Tolkien's, Wollheim knew what sold, and was happy to supply book-buyers with what he expected would sell. L. Sprague de Camp was another acquaintance of Tolkien's. They began corresponding in 1963 and Tolkien entertained de Camp at his house in February 1967, as de Camp was returning to the U.S. from a trip to the Middle East and India. Tolkien's acquaintance with Arthur C. Clarke and Sterling Lanier I have mentioned above, but one can also add Alan Garner's name to those connected to Tolkien. Garner was a student at Magdalen College, Oxford, in the mid-1950s, and has acknowledged that he met both Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, though Garner claims that Tolkien's writings had no influence on him. Many readers question this assertion.

Addenda: Thanks again to Dale Nelson, we now have three more entries for 1967. I don't have the months of publication for these titles, so the order given here is random. But all three are from Lancer Books, a mass market company that published around 2,000 titles from 1962 to 1973. The editor (after 1965) was Larry T. Shaw, who had edited a number of science fiction magazines in the mid-1950s. The first is L. Ron Hubbard's Slaves of Sleep (Lancer 73-573).

The requisite blurb is on the rear, and reads: "SLAVES OF SLEEP is a magic carpet into adventure, romance, fantasy, and dazzling color. It rates a place on your shelves next to the works of Tolkien, Burroughs, and Robert E. Howard."

The next is a book by arch-Tolkien basher Michael Moorcock, The Jewel in the Skull (Lancer 73-688). I don't have a scan of the back cover, where the blurb concludes: "a stirring new saga of swords and sorcery by a brilliant writer, the first of a series destined to rank with the Conan series and the Lord of the Rings trilogy."

And finally, another Conan book, The Hour of the Dragon (Lancer 73-572), by Robert E. Howard and edited by the ubiquitous L. Sprague de Camp. The blub on the front cover reads (somewhat ungrammarically): "Howard's only book-length novel, worthy to stand beside such heroic fantasy as E. R. Eddison and J. R. R. Tolkien."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)