The iconic list (or at least the starting point) for a

definitive bibliography of all of the titles in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy

series is the one by Lin Carter which appears as “Bibliography II” in his book Imaginary Worlds, published in June

1973, itself a volume of the series. Carter lists 57 numbered volumes of the

series, as published from May 1969 through May 1973. The series would officially last one further

year, bringing the official total to 65 volumes.

But Carter’s list, even when extended with the further

official titles, doesn’t cover outliers that, for one reason or another, seem

like they should be considered as part of the series. There are three main

types of potential outliers—fantasies published by Ballantine 1) before the

series; 2) during the series, and 3) after the end of the series. Carter began

his Bibliography in Imaginary Worlds

by listing sixteen such precursors, noting “they are all books I would certainly

have urged Ballantine to publish.”

I will consider these sixteen titles first, and list them

here with Carter’s numbering.

1. J.R.R. Tolkien, The

Hobbit [published August 1965]

2. J.R.R. Tolkien, The

Fellowship of the Ring

3. J.R.R. Tolkien, The

Two Towers

4. J.R.R. Tolkien, The

Return of the King

5. J.R.R. Tolkien, The

Tolkien Reader

6. E.R. Eddison, The

Worm Ouroboros

7. E.R. Eddison, Mistress

of Mistresses

8. E.R. Eddison, A

Fish Dinner in Memison

9. J.R.R. Tolkien and Donald Swann, The Road Goes Ever On

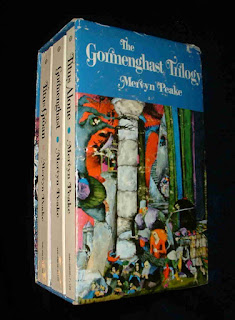

10. Mervyn Peake, Titus

Groan

11. Mervyn Peake, Gormenghast

12. Mervyn Peake, Titus

Alone

13. David Lindsay, A

Voyage to Arcturus

14. Peter S. Beagle, The

Last Unicorn

15. J.R.R. Tolkien. Smith

of Wootton Major & Farmer Giles of Ham

16. E.R. Eddison, The

Mezentian Gate [published April 1969]

The J.R.R. Tolkien books (nos. 1-5, 9 and 15) were never

published under the imprint of the unicorn’s head logo, but some of the others

were.

|

| Seventh Printing: September 1973 |

Of the E.R. Eddison books (nos. 6-8, and 16), the U.S. “Seventh

Printing (September 1973) of The Worm

Ouroboros is the only printing of any of the titles with the unicorn’s head

logo. The first U.S. printing of The Mezentian Gate, however, is marked

“A Ballantine Adult Fantasy” in small print running up the spine on the upper

cover (it appeared in April 1969, the month before the series proper started). All four Eddison titles were advertised and sold

in their Pan/Ballantine editions as part of the Pan/Ballantine Adult Fantasy

series, though they did not have the unicorn’s head logo.

|

| Fourth Printing: September 1973 |

Mervyn Peake’s books (nos. 10-12) have the unicorn’s head

logo only on two U.S. printings of each of the three books: the “Fourth Printing: September, 1973” and

the “Fifth Printing: January, 1974”. The

Peake titles were not published in the Pan/Ballantine Adult Fantasy series,

because the U.K. rights were held by another publisher, Penguin Books, who

published editions of all three books in 1968, 1969 and 1970, respectively. The

Penguin editions were reprinted a number of times over the next several years.

|

| Second Printing: April 1973 |

Two U.S. printings of David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus have the unicorn’s head logo on the cover, the

“Second Printing: April, 1973 (SBN 345-03208-X) and the “Third U.S. Printing:

September, 1973” (SBN 345-23208-9). The

Pan/Ballantine edition of March 1972 (SBN 345-09708-4) has the unicorn’s head

logo on the front cover; the second U.K. printing from 1974 (330-24057-9) has

not been seen.

|

| Fourth Printing: October 1972 |

As for Peter S. Beagle’s The

Last Unicorn, the unicorn’s head logo appeared on the “Fourth Printing:

October, 1972”, probably on the “Fifth Printing: February 1973” [not seen], and

definitely on the “Sixth Printing: September, 1973” and “Seventh Printing:

February, 1974.” Also, the phrase “A

Ballantine Adult Fantasy” appears in small print running up the spine on the

upper cover, on the first printing (February 1969) through the third printing

(November 1970).

|

| First Printing: February 1969 |

The Ballantine edition of Peter S. Beagle’s novel A Fine and Private Place also preceded

the series proper. It came out in February 1969, but that the author was Beagle

and that the cover art is by Gervasio Gallardo make it of interest to fans of

the series. Also, as with The Last

Unicorn and Eddison’s Mezentian Gate,

the words “A Ballantine Adult Fantasy” appear in small print running up the

spine on the upper cover.

|

| First Printing: March 1969 |

Carter’s list excluded his own Tolkien: A Look Behind “The Lord of the Rings,” “First Printing:

March, 1969,” which came out just before the series started. It is not usually

considered to be part of the series, but it is probably of interest to most

fans of the series.

Next come the various titles published by Ballantine while

the series proper was ongoing (May 1969 through April 1974) that have some

elements in common with the Ballantine

Adult Fantasy series, but which were never considered as officially part

of the series.

|

| First Printing: February 1971 |

H.P. Lovecraft. Fungi

from Yuggoth and Other Poems. “First Printing: February, 1971”

This is a retitling of Lovecraft’s Collected Poems (1963), as edited by August Derleth and published

by Arkham House. The Ballantine Adult

Fantasy series published other Lovecraft title, with cover art (as here) by

Gervasio Gallardo.

|

| Second Printing: February 1971 |

H.P. Lovecraft and August Derleth. The Survivor and Others. “Second Printing: February 1971” This title was first published by Arkham House

in 1957, and Ballantine published a first printing in mass market paperback in

August 1962. For this Second Printing, a new cover was commissioned from

Gervasio Gallardo. That these stories are bylined as “by H.P. Lovecraft and

August Derleth” is a fraud. They were

entirely written by Derleth, who claimed them to be “posthumous collaborations”

based on notes by Lovecraft, but these notes were (when discernable) minor idea

fragments that barely resemble the stories Derleth wrote.

|

| Fourth Printing: November 1971 |

Sometime, Never (“Fourth Printing: November, 1971”) was

originally published by Ballantine in June 1957. It consists of three tales of “science

Fantasy” by William Golding, John Wyndham, and Mervyn Peake. It was reprinted

in September 1957, November 1962, and in November 1971 when it was given a new

cover by Gervasio Gallardo. The classic

Peake story, “Boy in Darkness,” and the Gervasio Gallardo cover make it of

special interest to fans of the series.

|

| First Printing: November 1971 |

Isidore Haiblum. The

Tsaddik of the Seven Wonders. “First Printing: December, 1971”. This title is occasionally erroneously

included in lists of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, but it had only one

printing, and it never had the unicorn’s head logo on it. It is called by the

publisher on the cover a Science Fantasy Novel.

The cover art is by David McCall Johnston, who did other covers in the

Ballantine Adult Fantasy series proper.

|

| First Printing: February 1972 |

Lin Carter. Lovecraft:

A Look Behind the “Cthulhu Mythos.”

“First Printing: February, 1972” Of

Carter’s three works of nonfiction published by Ballantine, his Tolkien book preceded the Adult Fantasy

series proper, and his Imaginary Worlds

book was included as part of the series. Why his book on Lovecraft was not

included in the series is unknown, but beside Carter’s authorship, and the subject,

the cover art is by Gervasio Gallardo, and these three points make it of

interest to fans of the series.

Finally, the last of the outliers come from June to November

1974, and comprise two books published after retirement of the unicorn's head logo. These were originally intended for the series

before it was cancelled. The first has a Carter introduction and the second

completes a set of four begun during the series proper.

|

| First Printing: June 1974 |

H. Warner Munn. Merlin's

Ring. “First Printing: June, 1974” Munn’s book was clearly intended for the

series, as it has the usual Lin Carter introduction proclaiming it to be in the

series, and the wraparound cover art is by Gervasio Gallardo. It is among Gallardo’s

very best. There remains a small white

circle on the front cover, here filled with the words “First Time in Print” but

which was likely intended to house the usual unicorn’s head logo. A volume of

associational interest, Merlin’s Godson

by H. Warner Munn, came out as a “Ballantine Fantasy” with a gryphon logo on

the cover in September 1976. It contains two prequel novellas, “King of the

World’s Edge” and “The Ship from Atlantis,” originally published in 1939 and

1967 respectively.

|

| First Printing: November 1974 |

Evangeline Walton. Prince

of Annwn. “First Printing: November, 1974” This is the final volume of

Walton’s reworkings of the four branches of the Mabinogion. The first three

were published as part of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series proper, and

doubtless the fourth volume would have been too, if the series hadn’t ended

some six months earlier. And instead of

an introduction by Lin Carter, Prince of

Annwn has a puff piece from an article by Patrick Merla published in a

November 1972 issue of The Saturday

Review, that was also used to replace Carter’s introductions in the other

three volumes as they had been reprinted.

The cover art is by David McCall Johnston, who also did the cover art

for the second and third volumes of Walton’s series.

|

| First Printing: July 1975 |

Also of interest to readers and collectors of the series is

the one-volume edition of William Morris’s The

Well at the World’s End which was published in July 1975 (345244826 $2.95), and reprinted in May 1977 (now labelled

a “Ballantine Fantasy Classic,” 0345272390

$2.95), which uses two panels of Gervasio Gallardo’s art from covers of

the two volume edition.

Any one care to suggest other possibilities?

Please do so in the comments below.

Update (8/26/18): Per the second comment below, I add here the cover of

Tales of a Dalai Lama by Pierre Delattre, published by Ballantine in January 1973 (345030486 $1.25), cover art by Philippe Gravesz.

|

| First Printing: January 1973 |

Update (9/29/18): Here's another outlier of interest. For the sixth printing (June 1969), the seventh (January 1971), and the eighth (July 1971), Ballantine used a Bob Pepper cover on the classic Ray Bradbury collection

The October Country (first published in mass market paperback by Ballantine in April 1956):

Update (2/2/2026). Another Bob Pepper cover from the July 1971 printing of

Fahrenheit 451.

Since the publication of Verlyn Flieger's edition of The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun in 2016, there has been much renewed attention to Tolkien's five-hundred and six line poem, originally published in The Welsh Review in December 1945. Little notice, however, has been made of the fact that the original Breton poem was sung to a ballad. Last year I got a copy of Miracles & Murders: An Introductory Anthology of Breton Ballads (Oxford University Press, 2017), by Mary-Ann Constantine and Éva Guillorel. Besides a long introduction, this anthology contains some thirty-five Breton ballads (or gwerz), with musical scores, and, most significantly, a CD containing recordings of twenty-two of the ballads.

Since the publication of Verlyn Flieger's edition of The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun in 2016, there has been much renewed attention to Tolkien's five-hundred and six line poem, originally published in The Welsh Review in December 1945. Little notice, however, has been made of the fact that the original Breton poem was sung to a ballad. Last year I got a copy of Miracles & Murders: An Introductory Anthology of Breton Ballads (Oxford University Press, 2017), by Mary-Ann Constantine and Éva Guillorel. Besides a long introduction, this anthology contains some thirty-five Breton ballads (or gwerz), with musical scores, and, most significantly, a CD containing recordings of twenty-two of the ballads.